Murder by the Blade

Murder by the Blade

Washington Post, The (DC) - October 1, 1980

Author: Gary Arnold

The newspaper ads for "He Knows You're Alone" and "Schizoid" are almost identical, the dominant motif being a dark silhouette with a sharp weapon (knife in one case, scissors in the other) gripped in its fist. The copy also overlaps: "The wedding night killer is about to strike again!" contrasts with "Dear Julie: Don't let me do it again . . ."

Obviously a similar MO. And at the theater where I sampled "Schizoid" over the weekend, lobby posters for the upcoming "Terror Train" and returning "Prom Night" quadrupled the stabbing imagery.

Despite the impression of bloodthirsty uniformity, these movies have been far more distinctive in mood and technique than, for example, porn features or the genre of raunchy farces spawned in the wake of "National Lampoon's Animal House," More often than not, murder thrillers exhibit an authentic flair and gusto, suggesting that they supply the least expensive and most reliable pretext for aspiring talent.

If John Carpenter could earn a reputation as an exciting young stylist with a scare movie as elementary and ponderous as " Halloween ," then the unknown directors of "He Knows You're Alone" and "Schizoid" -- Armand Mastroianni and David Paulsen respectively -- merit instant cult acclaim and multiple-picture deals. They imprint a surprising amount of kicky, insinuating stuff on the screen, notably and aptitude for erotic comedy that needs a less frightening and under handed pretext to evolve in a consistently satisfying way.

It's curious that in both movies, the most shocking elements tend to receive the most derivative, cliched depiction, with the camera crudely stalking the victims while the sound track redundantly breathes down their necks. The directors can't afford to skip the violent pay-offs, of course, but they seem far more inventive and relaxed with the expository material that precedes and follows the atrocities.

In "He Knows You're Alone" the killer is identified relatively soon as a psycho whose specialty is terrorizing young women about to be married. Judging from the pile of victims he leaves behind, the homicidal urge is easily transferred to friends, acquaintances and by-standers. (In fact, a title like "He's All Over the Place" would be more appropriate.) I wish Mastroianni (a cousin of the famous Marcello but born and raised in New York) and screenwriter Scott Parker had used one of the lines echoed with creepy effectiveness in the course of their playful, verbally witty script: "Is Anybody There?"

"He Knows You're Alone" is the classier production and superior fright spectacle of the two. It opens with a deceptive, illusion-meet-reality murder sequence that combines hilarious and terrifying effects. Making a scintillating feature directing debut at the age of 30, Mastroianni reveals a special knack for juxtaposing funny and frightening stimuli, recalling De Plama and Steven Spielberg at their most provocatively amusing.

It's a safe bet that Mastroianni's cirriculum included "Carrie" and "Jaws" as well as "Psycho," which is casually discussed by one of the characters and twice emulated. "He Knows You're Alone" inspires sustained, high-decibel shrieking when Mastroianni cuts loose, but it ingratiates itself in a more congenial way by being so mischievosly movie-crazy and by swift strokes of characterizationand funny romatic by play.

Most of the characters -- including those seen or heard only momentarily -- create distinctive impressions. The apparent ease with which Mastroianni can achieve a humorous, diverse social atmosphere may carry him much further in the long run than the mechanics of pictorial terror, proficient as he is at souping up the jolts and shivers The menace seems more menacing because you're often charmed or tickled by the people in harm's way, notably Don scardino (the only recognizable human in "Cruising" not so long ago) as the affable ex-boyfriend of the imperiled heroine (caitlin O'Heany, effectively vulnerabvle in appearance but not quite adequate histrionically); Patty Pease as the heroine's liveliest pal, a sexpot with an infectiously brazen sense of humor; and Joseph Leon as the crusty, cigar-puffing proprietor of a bridal shop.

Mastroianni's exuberant talent doesn't necessarily save him from bad judgement. The killer seems to come and go with the freedom of a phantom and strike with the inhuman force of jaws or The Thing. A subplot involving a cop obessively pursuing the killer seems as misplaced as a dangling shirttail. If Mastroianni and Parker couldn't get it tucked in, they should have cut it off. Worst of all, the fadeout evocation of " Halloween " is a very dumb joke. o

"Schizoid" is a hapless title, and for the first reel or so it appears unlikely that the film will rise above its initial lurid homicide and low-budget veneer.

Neverthless, Paulsen succeeds in sustaining a mystery plot and showing flashes of intuitive directing ability in a ramshackle context. The hit in his movie consists of five women introduced sharing gossip and champagne in a hot tub. (Obvious overlooked title: "The Hot Tub Murders.") It's disclosed that the victims have something else in common: an ambiguously tormented group therapist played by Klaus Kinski, revealed to be romantically entangled with more than one female member of the group.

Perhaps the funniest line in the script occurs when murder has taken a toll of Kinski's patients, and he exclaims "Where is everybody?" (another swell title wasted) at a small turnout. The ultimate target is Mariana Hill, who writes a newspaper advice column, "Dear Julie." It's Julie's friends who get knocked off first, and the suspects are somehow connected with Julie.

At first every suspicion points rather too directly at Kinski. The rival suspects -- Craig Wasson as Julie's estranged husband and Christopher lloyd as a building suprintendent infatuated with Julie (hilariously, he's also a member of her group) -- don't receive nearly as much suggestive footage. Unexpectedly, Paulsen compensates for this weakness by springing a fourth suspect, who could be in a unique position to frame Kinski. s

Finally, in a deft climactic manuever Paulsen gets all four suspects and the heroine in the same deathrap -- her office -- at the same time. Having achieved this social coup, Paulsen begins cooking with a skill you couldn't have anticipated in the early reels. Throughout the denouement the suspense intensifies partly through the manipulation of clever ironic details like the timely use of the prevailing murder weapon, a pair of scissors, to help save the heroine's skin. When the final credits roll up you still feel slightly breathless from the whirlwind payoff.

Mastroianni and Paulsen haven't come to town with the most reputable vehicles ever made, but you leave convinced that they know how to get some exciting mileage out of those rattletraps.

Too Many 'Knights' in the Same Old Town

Too Many Knights in the Same Old Town

Washington Post, The (DC) - May 20, 1980

Author: Gary Arnold

The Hollywood Knights," the motleyest imitation yet of "American Graffiti," illustrates how rapidly decay can set in after a concept is generally recognized as appealing in Hollywood. The idea of "American Graffiti" was rejected by every major studio (and some twice) before finally being shot for the paltry sum of $800,000 and released successfully in 1973.

Its success inspired a popular TV series, "Happy Days," which then became the model for increasingly strained spinoffs and imitations. "American Graffiti" no doubt paved the way for fitfully interesting theatrical disappointments like "American Hot Wax" and "The wanderers." The derivative trail seemed to come to a dead and last summer when George Lucas himself collabrated on "More American Graffiti," a misbegotten sequel to his original triumph. With "The Hollywood Knights," Floyd Mutrux, the director of "American Hot Wax," seems determined to wear out the welcome of a once-amusing nostalgic device once and for all.

"Knights" relies on a soundtrack full of golden oldies to evoke the ostensible setting. Beverly Hills on the Halloween night, 1965. The members of a car club, the Hollywood Knights, cruise in and out of their favorite meeting place, a drive-in diner called Tubby's that is scheduled to close the following day, victimized by uptight residents and urban renewal.

The jerky, threadbare continuity is devoted to savoring the antics of the most irrespressibly clowish Knights, notably an obnoxious campus cutup called Newbomb, embodied by a smirky galoot named Robert Wuhl. Sort of a cheerless, vague reminder of Dick Shawn, Wuhl betrays the ill effects of too many appearances as a facetious would-be escort on Chuck Barris' "The Dating Game." He already resembles stale comic goods in his movie debut. Moreover, he appears so old for the role that one is left with the impression that Newbomb must have been repeating the 12th grade since about 1950.

Evidently destined for a career as the slimiest lounge comedian in Las Vegas, Newbomb celebrates this farewell Halloween by repeatedly humiliating other subspecies: Gailard Sartain (who played The Big Bopper in "The Buddy Holly Story") and Sandy Helberg as stoogy patrolmen; Leigh French and Richard Schaal as adulterous upper-middle-class hypocrites; Stuart Pank as a fat adolescent mama's boy. The Newbomb repertoire relies all too heavily on stinky chestnuts: food-chuckling, mooning, flatulence, even the old flaming dog doo on the front porch. He's got a handful of hot ones, does Newbomb.

The derivative ineptitude of Mutrux's burlesque humor is epitomized in his borrowing of the sight gag from the cover of the National Lampoon's High School Yearbook Parody. You'd think that moving pictures might do more with the idea of a pantyless cheerleader than a still photograph could, but Mutrux is so imprecise and inattentive that the forgetful (or exhibitionistic) cute isn't even caught from wittly revealing, decisive angles. Mutrux canan barely be trusted to get a laugh out of can't miss, pie-in-the-face situation.

Mercifully, not every Knight is supposed to be a card. There are subdued subplots dealing with a member about to join the Army (and presumably perish in Vietnam) and another (Tony Danza of "Taxi") at odds with his girlfiend (Michelle Pfeiffer), a carhop with dreams of a Hollywood career. Although it comes as a welcome change of emphasis, the "serious" motif is as superficial and perfunctory as the farce. Nothing takes hold within this spastically facetious, centrifugal filmmaking context. Moreover, the dialogue tracks seem so poorly recorded or mixed that the conversation is often reduced to incomprehensible static.

Mutrux is probably a genuine child of pop culture, and he showed some comic aptitude in "American Hot Wax." He's backpedaling in "Holloywood Knights," a disgraceful trifle predicated on an idea whose time has passed. Far from showing continued promise, Mutrux has now identified himself as a kind of untutored, remedical-school imitator of George Lucas.

' Halloween ': A Trickle of Treats

' Halloween ': A Trickle of Treats

Washington Post, The (DC) - November 24, 1978

Author: Gary Arnold

A most inappropriate Thanksgiving attraction, " Halloween ," arrives at a time when reports of an authentic horror story are bound to accentuate the triviality of a mere horror movie.

Not that this plodding exercise in sham apprehension would look impressive even if one felt starved for morbid stimulation. Now at area theaters, " Halloween " is far more proficient at torpor than terror.

Evidently conceived as a genre talent showcase by 30-year-old John Carpenter, who also collaborated on the minimal scenario and composed the undernourished score. " Halloween " is a stab at a derivative minor classic. It's apparent where Carpenter got his horror devices - and a minor misfortune that he hasn't been able to synthesize them in a fresh or exciting way.

The movie begins with a prologue in which a teen-age girl is stabbed to death in her room on Halloween night, 1963. The murder is depicted subjectively, supposedly from the point of view of the killer, who peeps at the girl as she necks with her boyfriend, extracts a butcher knife (inevitably reminiscent of the murder weapon in "Psycho") from a kitchen drawer, climbs a steep staircase (inevitably reminiscent of a key setting from "Psycho") and attacks the victim, who is unclothed and appears to recognize her assailant.

In a moment it's revealed why she knows him: the killer is the victim's kid brother, dressed in a clown's costume. This kicker is the sort of "masterstroke" that makes the crime itself look clownishly implausible, but Carpenter blunders on. It's 15 years later, Halloween Eve, 1978. Two passengers in a car navigating through a rainstorm (inevitably reminiscent of a situation in "Psycho") are entrusted with cryptic expository lines updating the murderer's case history.

The passengers are a psychiatrist, played by Donald Pleasence, and a nurse. According to the physician, the killer was a child of six when he stabbed his sister and has failed to respond to treatment while growing up in an institution for the criminally insane. He is convinced that this bad seed, named Michael, will always be a menace - indeed, the essence of evil. He is determined to impress this fear on a parole board scheduled to review Michael's case.

Arriving at the institution to pick up Michael, doctor and nurse discover that he's been waiting for them. In fact, he steals the car from under their negligent noses and heads for the scene of the crime, Haddonfield, Ill., an idyllic small town obvioulsy chosen to duplicate Hitchcock's use of pretty, serene Santa Rosa, Calif., as a backdrop for terro in "Shadow of a Doubt."

Once back home, the grown Michael, whose face remains averted from the camera, branches out a bit, recalling sources other than Hitchcock. He begins stalking potential victims derived from Brian DePalma's "Carrie" - high school girls played by Jamie Lee Curtis. P. J. Soles and Nancy Loomis - and affecting a heavy mockasthmatic wheeze borrowed from the maniac played by Ross Martin in Blake Edwards' "Experiment in Terror."

Since there is precious little character or plot development to pass the time between stalking sequences, one tends to wish the killer would get on with it. Presumably, Carpenter imagines he's building up spinetingling anticipation, but his techniques are so transparent and laborious that the result is attemuation rather than tension.

Carpenter lacks the stylistic flair and psychological penetration that have allowed De Palma and George Romero to contribute new classics to the horror in recent years. Carpenter's scenario isn't rooted in anything except old movies, and it develops too arbitrarily to establish roots even in that shallow ground.

Michael's case history doesn't sustain the movie beyond the prologue. The killer has no identity as a dangerously demented human being. He's a thing lurking in the dark, the bogeyman that a neighborhood kid takes him to be.

Moreover, that darkness is so Stygian that it's often impossible to discern anyone's face or appreciate the monster's unexpected entrances. The murky images are the closest Carpenter comes to giving the picture a "look," and it turns out to be a self-defeating one, similar to the lighting miscalculations that seem to be plaguing many movies these days, especially "Comes a Horseman" and the still unreleased "September 30, 1955," both shot-by Gordon Willis and both literally lost in the dark for long, long stretches.

Eventually, Carpenter's dimly perceived bogeyman degenerates into a bad joke. After snuffing the high school girls played by Soles (who appeared in "Carrie" as the best pal of bad girl Nancy Allen) and Lomis - whose promiscuity apparently renders them expendable - Michael is confronted by the straight-arrow character of Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis but more suggestive of a melancholy, ungainly young Lauren Bacall).

The movie ends with the sound of heavy, heavy breathing still haunting the pleasant tree-lined streets of Haddonfield. A horror melodrama that resorts to an "irony" like that obviously wants to be congratuled for digging its own grave. Congratulations.

"Rolling Thunder": Twisted Violence

"Rolling Thunder": Twisted Violence

Washington Post, The (DC) - October 29, 1977

Author: Gary Arnold

John Flynn's crisp, laconic direction and evocative use of Southern Texas locations - the San Antonio area, with particularly effective, sinister excursions to border towns like Del Rio - transorm "Rolling Thunder," now at area theaters, into a more distinctive exploitation movie than it deserves to be. The screenplay, which originated with Paul Schrader, the writer of "Taxi Driver," is miserably vicious, a hybrid of "The Wild Bunch" and "Death Wish" in which a returning P.O.W., an Air Force major who spent eight years imprisoned in North Vietnam, sets out to massacre a gang of hoodlums who break into his home, shove his right hand down a churning garbage disposal and shoot his wife and son.

The premise is twisted in a way that could serve as a textbooks example of pornographic violence. All the major's ordeals - physical and emotional, as a prisoner and a returning serviceman and family man - become pretexts for kinked-up, brutal sensations and a final orgiastic shooting spree.

There's no point in responding to the hero's situation with ordinary sympathy or human interest, because these amount to sucker's responses in this context. Flynn directs the homecoming encounters between William Devane as the major, Hordon Gerler as his son and Lisa Richards as his wife, who has become romantically involved with another man, with such admirable stillness and concentration that one could be fooled into believing that the film intends to deal with his readjustment problems conscientiously. In retrospect, one may recall this as the neatest single illusion in the picture and wish John Flynn a more appropriate subject for stylistic concentration the next time around.

it doesn't take long to discover that the humanistic murmurs are setting up nihilistic knock-out punches. Bringing on the murderers spares a screenwriter the drudgery of trying to resolve the estrangement between the major and his wife. At the same time it's presumed to give a melodramatic warrior a "mission" worthy of his training and value system. Yet there's no conviction behind this mission of vengeance, no sense of values that might deserve to be protected or offenses that might deserve to be punished.

On the contrary, the hero and a fellow P.O.W. who joins him, played by Tommy Lee Jones, are justified on the basis of professionalism rather than motive. We're supposed to accept the platitude that they're emotionally dead and have been since their capture during the war. The major has become a stranger to his family, and while he's offered a girl friend who might be some consolation - Linda Haynes, who resembles a careworn Tuesday Weld, makes an appealing impression as a cocktail waitress whose down-to-earth aspirations and apprehensions correspond to the audience's - he must reject her, or else miss the climactic shootout.

The major's comrade leaves a household conceived as the meanest of lower middle-class sancturaries, a haven for prattling women and unheroic men. In its simultaneous contempt for the homefronts the heroes ostensibly march out to avenge or protect and for the scummy adversaries they'll face, the movie exposes an emotional and moral blackout far more genuine than the perfunctory daze ascribed to Devane and Jones, both very capable actors. This picture was conceived by someone - presumably Schrader - who glorifies violence, yet only responds to it as a transcendant, abstract pictorial spectacle, an esthetic thrill, like the nomcombatants who derive more satisfaction from combat than professional soldiers.

There are some exceedingly ugly notions in "Rolling Thunder," and they're never mitigated by the kind of character exploration and embiguity that strengthened "Taxi Drive." For example, the major is depicted recalling nightmarish scenes of torture and then reenacting some of those scenes, with a hint of of masochistic gratification. His severed hand is replaced by a prosthetic device that becomes even better than a hand for the purposes of this story, because he can file the to a point and use it as a deadly weapon.

The big showndown self-sconsciously justaposes sex and violence. The setting is a Mexican bordello, so naked actresses scurry about trying to stay out of the line of fire while the actors pretend to have it out. Speaking of having it out, Jones is depicted being undressed by a whore seconds before the shooting starts, and he comes out of her room with an automatic rifle in one hand while zipping up his fly with the other. "Rolling Thunder" is undoubtedly Spawn of Peckinpah, but some of its kinkier wrinkles might shock the originator himself.

'Telefon': Dialing for Spies

'Telefon': Dialing for Spies

Washington Post, The (DC) - December 17, 1977

Author: Gary Arnold

"You must admit it's ironic, the KBG sending you to protect the American Establishment," says Yankee accomplice Lee Remick to Soviet secret agent Charles Bronson late in "Telefon," a new espionage melodrama at several area theaters.

This line says a lot, since it reflects the movie's uncertainty about whether the audience has been witty enough to appreciate the filmmakers' little detente-in-spired joke of casting Bronson as a Soviet spy trying to prevent a renegade colleague, Donald Pleasence, from provoking World War III with acts of sabotage in the United States.

The real problem is that the filmmakers lay out this story blueprint so doggedly that the audienfe is invariably 25 pages of expository chitchat ahead of them. Following "Telefon" is about as thrilling as being kept on hold for the better part of the day.

The title refers to a telephone-activated sabotage network supposedly by the KBG back in the early '60s. If worse came to worst, about 50 agents long since submerged in ordinary American identities and walks of life could be triggered into carrying out strategic acts of sabotage in the manner popularized by "The Manchurian Candidate" - hearing a code phrase that compels them to obey hypnotically implanted commands.

There's a tension-eliminating goofiness about the premise from the outset. KBG biggies Patrick Magee and Alan Badel turn to Bronson, the superspy with the photographic memory, because they don't want to 'fess up to Brezhnev; assuming the Telefon project had become obsolete, they didn't tell him about it. As a matter of fact, it probably is obsolete, they didn't tell him about it. As a matter of fact, it probably is obsolete. Pleasence can't retarget the human missiles he activates. In the first of these suicide missions we're invited to see a Denver gas stateion owner blow up what used to be a Chemical-Biological Warfare storage depot.

Upon his arrival Bronson is contacted by Remick, an American liaison who rivals Pleasence as a candidate for instant liquidation in my book. Supposedly assigned to assist Bronson, she immediately begins to henpeck him prattle and demands for equality. But the filmmakers have a surprise up their sleeves, eventually played with no flourish, that they think explains her presumptuous conduct.

In my naive way, conditioned by so many years of stories in which characters with apparent affinities were brough together and clues were systematically followed up, I kept expecting Bronson to be matched with the likable woman on the premises, a brainy CIA researcher played by Tyne Daly (who also brought an ingratiating note of humanity to the last Clint Eastwood vehicle. "The Enforcer"). I still see no compelling reason why the paths of the American office worker with the fabulous memory and the Russian field operative with the fabulous memory shouldn't cross.

The script credited to Peter Hyams and Stirling Silliphant tends to inspire unintentional mirth at least from the moment one hears the ominous code phrase - a passage from Robert Frost's "Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening." Still, they have a way to go before matching the editorial writers at Izvestia, who handed the film company a publicity bonus when "Telefon" was shooting in Helsinki, which doubled for Moscow.

The Izvestia salvo couldn't have been wilder: "It is obvious that the film has a provicative character. Its purpose is to stroke up a psychosis against the Soviet Union in western countries. . . The wires from this 'Telefon' lead back notorious western intelligence agencies which use every dirty method in their anti-Soviet activities."

Director Don Siegel joked that he expected to be summoned to the Kremlin and awarded a decoration after the movie came out.

He can dream, but no one will be pinning decorations on him for the quality of "Telefon." If anything, Siegel's style of direction seems to be slowing to an irreversible plod.

'The Choirboys': An Out-of-Tune Precinct

'The Choirboys': An Out-of-Tune Precinct

Washington Post, The (DC) - December 24, 1977

Author: Gary Arnold

Among the Los Angeles patrolmen characterized - or, to be precise, caricatured - in "The Choirboys," now at area theaters, the term "choir practice" is a euphemism for an all-night drunken toot in MacArthur Park. At some stage the original author, Joseph Wambaugh, and the director, Robert Aldrich, must have envisioned a profane popular comedy patterned after "M*A*S*H," with the choir practicesserving the same purpose for overworked, pressured and sometimes brutalized urban cops that the binges and practical jokes served for the battle surgeons in Robert Altman's film.

"The Choirboys" belongs to the tradition of service comedies, but I doubt if anyone will hail it for doing a service for either cops or movie auidences. If the filmmakers had ironic or satirical intentions, the finished film totally obscures them. There's no contrast between cops at work and play. The whole movie suggests a dirtyminded "McHale's Navy," with scenes pivoting on gross set jokes alternating with scenes pivoting on grosser sick jokes.

Some of the jokes are so raucously or goofily low-minded that you may laugh out of a kind of shocked weakness. At a certain level there is something funny about the idea of a drunken slob creeping under a glass-topped coffee table to get a peek up a women's skirt or the idea of a jumper being provoked to her doom by a cop who tries to use reverse psychology and dares her to "go ahead and jump."

However, once commiting your entertainment in this direction, it may be impossible to change. Towards the end "Choirboys" attempts to get serious about the sordidness that it has been wallowing in for gratuitious, episodic laughs, and this switch seems both deceitful and laughable. It's much too late to take a different tack, and at the fadeout the mood returns to cackling facetiousness. The promotion for this movie should probably be built mately, neither the filmmakers nor the characters feel any credible pain. They're just rowdy fraternity boys in blue.

Wambaugh, who did the original adaptation of his own best-selling novel, has been busy disowning the film. He succeeded in having his name removed from the screenwriting credits and placed an ad in movie trade papers complaining that Aldrich had done him wrong. It's difficult to see how. The comic vulgarity originated in the novel, and surely no one could imagine the director of "The Dirty Dozen," "The Longest Yard," "Hustle" "The Killing of Sister George" and "Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?" suddenly developing a delicate touch.

It's more likely that Wambaugh came to the realization that visualizing this colection of tales told out of school could be more embarrassing and misleading than simply publishing them. "The Choirboys" is a vaudeville of precinct scandals and follies that may not mean the same thing to cops that they mean to civilians. Although he supplied the pretext and context, Wambaugh may not care to associate himself with the misconceptions about police work and psychology that could result from the film version.

"The Choirboys" takes a fairly obnoxious place among a burgeoning genre of Hollywood films determined to revel in raunchiness. "Slap Shot" set, the pace earlier this year. Now we have "Looking for Mr. Goodbar," "Saturday Night Fever," "The Gauntlet" "The Choirboy" and even "The World's Greatest Lover" straining to keep up, The spectre of television must be partly responsible: To a certain extent these movies recommed themselves because they'll need to be expurgated for telecasting.

Charles Durning has the most prominent role in a large, able but largely wasted cast as the hard-bitten patrolman "Spermwhale" Whalen, suggesting a cross between Spencer Tracy and Los Costello. Not too surprisingly, Burt Young creates the most human and appealing impression as a motley-looking but gentle natured vice cop. Tim McIntire also gets something distinctive into the boobytrapped assignment of the resident redneck bigot. Robert Webber cops the booby prize for his teethgrinding closeups as, naturally a mealy-mouthed brasshat.

'DEMON SEED': A Computerized Horror

'DEMON SEED': A Computerized Horror

Washington Post, The (DC) - April 8, 1977

Author: Gary Arnold

"Demon Seed," now at area theaters, pioneers and esoteric sex crime, computer rape, and blends it with the hit atrocity from "Rosemary's Baby" - infernal conception. Julie Christie has been lured into the thankless starring role of the victim, the estranged wife of computer designer Fritz Weaver, whose awesome new electronic brain. Proteus IV, the repository of literally all knowledge, gets an uncontrollable hankering to reproduce itself in human form and fixes on Christie as semi-Freudian mate bait.

Norminaly, the film is a science-fiction thriller about sexual terror, but it's governed by an attitude that minimizes the terrifying or suspenseful possibilities. Ultimately, director Donald Cammell seems to be proselytizing for crossbreeding between humans and machines, which is viewed as potentially Great Leap Forward in evolution.

They may not realize it, but Cammell and the other men who engineered this story - novelist Dean R. Koontz and screenwriters Robert Jaffe (the offspring of the producer, Herb Jaffe) and Roger O. Hirson - have failed to identify with their ostensible protagonist. Casting the sullen, hard-faced Christie as a Leda of the Computer Age seems an unconscious giveaway, because Christie became a star playing a spiteful, amoral girl who degraded herself and has never really transcended that image.

As a terrorized heroine, she doesn't evoke the immediate sympathy of actresses like Ingrid Bergman in "Gaslight," Dorothy McGuire in "The Spiral Staircase," Audrey Hepburn in "Wait Until Dark" or Mia Farrow in "Rosemary's Baby." One tends to associate Christie with girls who'll try anything once, so she seems ill-equipped to arouse pity and terror by pretending to spawn a metallic-looking Uberkind at the urging of a presumptuous machine that sounds like Robert Vaughn.

The filmmakers' crackpot transcendentalism, possibly inspired by that blasted embryo-in-the-cosmic-bubble image at the end of "2001," prevents them from taking the heroine's violation seriously in either human or melodramatic terms. In a scene that might have been irresistibly funny in a different context, Christie is shown with a rare smile on her face after being impregnated by Proteus IV, which puts her in the mood with computer animation designed by Ron Hays of M.I.T.'s Center for Advanced Visual Studies.

Like the rapacious computer, whose brain waves are illustrated with excerpts from the work of the great abstract animator Jordan Belson (Cammell has stylish taste in abstract imagery and deplorable taste in abstract thought), the filmmakers demonstrate perfunctory concern for the heroine's fears and protestations but ultimately dismiss them as short-sighted. The poor, skittish creature can't seem to grasp the honor of being used as an evolutionary guinea pig, the mother of a potential master race yet.

"Demon Seed" might have been a genuinely witty and terrifying thriller if someone had taken advantage of the story's glaring sadomasochistic implications. Nevertheless, Cammell plays it dumb at a thematic level, ignoring the sci-fi sexual bondage satire staring him in the face.

Proteus ought to be acting out the unconscious or half-conscious desires of his creator, a spurned and frustrated mad-scientist husband. Cammell establishes the fact that the Weaver-Christie marriage is on the rocks. But having established this conflict, the filmmakers neglect to exploit it. What might have become an ingenious parable about the battle of the sexes ends up a dopey celebration of an obstetric abomination.

There couldn't have been much feminine input during "Demon Seed." Cammell doesn't seem to be aware of how this computer-conrolled act of subjugation could be linked with more commonplace apprehensions. For example, a little conversation with new or expectant mothers might have alerted him to the fact that women often feel more threatened than reassured by the counsel they receive form supposedly authoritive males, particularly in the medical profession.

BILLY JACK: Running His Act Into The Ground

BILLY JACK: Running His Act Into The Ground

Washington Post, The (DC) - May 12, 1977

Author: Gary Arnold

While "Billy Jack Goes to Washington" never sounded like the most thrilling coming attraction of 1977, I expected a few more laughs and self-righteous outrages than the plodding, stuffy finished product, now at a trio of K-B theatres, has to offer.

Not that Tom Laughlin and Delores Taylor have totally missed the old funnybone in the course of inserting those progressively insufferable characters, Billy Jack and Jean Roberts, into the screenplay of Frank Capra's 1939 rabble-rouser, "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington," nominally updated and rewritten to accomodate their own rabble-rousing formula.

One feels a tug in the right direction when Elmer Bernstein selects "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" to underscore one of daughter's speeches as the newly appointed Senator Billy - a description of his pet project, a national camp for abused children.

When Billy asks, "How would you youthful, overwhelmingly nubile staff members chorus their approval "yeah!" shouts one and "All right!" cries another - one almost anticipates a production number in the tradition of the Judy Garland-Mickey Rooney musicals. Alas, none materializes. Director Laughlin, alias T. C. frank, keeps the cast sitting around inflicting interminable speeches upon one another.

Only Delores Taylor could bring the appropriate note of doleful complacence to a construction like the following: "It's still the same old story, isn't it, Senator? As soon as someone tries to buck up against a big organization, the little guy just doesn't stand a chance, does he?" There will be no rest in high places when it's learned that "Billy Jack's Little Raiders are digging up some things on the whole nuclear program that are making people nervous, including people at the White House guys like to write a bill?" and his . . ." or that "The groundswell for Billy Jack is dangerous. Just let him link up with Nader or Gardner and he'd be unstoppable."

On the contrary, Laughlin and Taylor have virtually stopped themselves by running their act into the ground. Laughlin should have realized how superfluous it was for him to remake "Mr. Smith" literally. For all intents and purposes he had remade it after completing "Billy jack," which resurrected most of the impassioned virtues and sentimental, slightly hysterical defects of the Capra movie in an early '70s context.

Unlike its solemn sequels, "Billy Jack" even benefitted from leavening touches of humor in the Capra tradition.The film's success evidently prompted Laughlin and Taylor to elevate the characters of stalwart Billy and haggard, do-gooding Jean into pop culture sacred cows. After the sanctimonious excesses of "The Trial of Billy Jack" in 1975, there was nowhere for the series to go. It would have been more logical to establish a Church of Billy Jack than shoot another Billy jack movie.

Laughlin relies so heavily on the original plot and dialogue of "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington" that one may feel a little embarrassed on his behalf. It's obvious that he's used the Capra film as a crutch rather than an inspiration. If "Billy Jack Goes to Washington" isn't a word-for-word "adaptation" of the screenplay Sidney Buchman wrote for Capra, it's close enough to pose the question, Why not revive "Mr. Smith" itself?

Laughlin bloats the running time by tacking on certain Billy Jack speeches and shtiks, including one brief display of hapkido, inflicted on a gang of threatening blacks whose possibly disquieting racial makeup is blithely rationalized by pretending that the CIA or FBI must have wanted it that way.

I had been wondering how Billy Jack, who served time between "Billy Jack" and "The Trial of Billy Jack," could reach the Senate in the first place. Laughlin has an explanation for that: Billy is granted a full pardon by governor Dick Gautier, who appoints him to fill out the term of Kent Smith, a senator who seems to succumb to questioning by argumententative reporters. There's no explanation for Jean Roberts' amazing recovery from what appeared to be permanently crippling injuries in "Trial." Oh, well, you can't expect everything in a talky, static, derivative picture that seems to run on forever. Frank Capra Jr., the producer of "Billy Jack Goes to Washington," may be considered out of the running for this year's Honor Thy Father Award.

'THE CAR': A Real Lemon

'THE CAR': A Real Lemon

Washington Post, The (DC) - May 16, 1977

Author: Gary Arnold

Clinkers as resounding as "The Car," now sputtering about several area threaters, might be avoided if the film executives reponsible for approving their production were immediately subject to certain penalties. For example, they might be compelled to reimburse deluded exhibitors out of their own pockets for any advances extracted on the implict understanding of supplying a presentable attraction. Or they might be required to defend their handiwork before crowds of derisive customers.

It's impossible to believe that "The Car," a bumptious horror melodrama about a driverless demon vehicle that terrorizes a Utah town, ever impressed anyone as an original or venturesome project. It's a blatant, pitiful attempt to recycle elements from superior scare vehicles - Steven Spielberg's television movie "Duel," which made a good deal of money for Universal in theatrical release abroad, and Spielberg's "Jaws," which has earned the company rentals of $200 million in less than two years.

Under the circumstances, Unversal should be the last distributor which finds it necessary to bankroll a rip-off like "The Car," which should probably be called "Fenders." There's no telling how many sounder, wittier scripts, including stories in the same genre, might have been overlooked or rejected in order to waste time and rejected in order to waste time and resources on this feeble in-house imitation.

Poor James Brolin! After all those dutiful, stultifying years as protege to Marcus Welby, what is his big-time movie reward? "Gable and Lombard" followed by "The Car." In the latter Broling and Ronny Cox, cast as the lawmen who must protect their loved ones and community from a motorized demon, wear permanently pained expressions.Cox is meant to be feeling guilty because he's taken to the bottle again, but it's easier to believe that he's just realized how awful his material is. Brolin punctuates his scowing inner torment with breathing exercises that expand his chest incessantly if not quite heroically.

The cast members might be wise tostart cultivating gags about their work in "The Car," since it's likely to remain the low point of their careers. At least one hopes so. The director, Elliot Silverstein, seems to have dedicated his career to making fools out of all the people who predicted great things from him after "Cat Bailou." He can't seem to handle anything skilfully in "The Car."

What could he have instructed the actors assembled for the denouement, in which Brolin supposedly lures the car to a fiery doom? Did he really ask for the hilarious set of bug-eyed, cringing reactions documetned on the screen? How can you set up a spectacular visual shock, like the shot of the car's headlights approaching out of the distance straight toward a living room window, the heroine and us, and then defuse it by switching to oblique angles right before the moment of impact? Every would-be scarifying highlight in the picture is undercut by disjointed editing maneuvers or inexplicable trick effects.

Of course, the premise is not exactly foolproof. If something as tangible and mechanical as a customized limousine (designed by George Barris, the noted customized limousine (designed by George Barris, the noted customizer who was one of Tom Wolfe's subjects in "The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby," on the chassis of a Lincoln Mark III) is going to be on a supernatural rampage, a certain cleverness or finesse would be desirable in both the writing and directing departments.

There's nothing under the surface either, no pattern or primitive fear mechanism guiding the car. What you see is what you get, and it deserves to be thrown back.

Promising, Precocious 'LITTLE GIRL'

Promising, Precocious 'LITTLE GIRL'

Washington Post, The (DC) - May 17, 1977

Author: Gary Arnold

"The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane," set in a New England sea-coast town but actually shot in Quebec two years ago as a Canadian-French re-production, stars Jodie Foster in a role that takes some advantage of her unique, impressive precocity - a self-reliant 13-year-old who attempts to sustain a solitary, independent existence by concealing the death of her poet father.

Ultimately, this account of a bright child's peculiarly dangerous social deception is confined within murder mystery bounds that are too glib, too imorally contrived, to be satisfying. The young heroine is burdened with more skeletons in her closet than she needs if her plight is to remain credible and sympathetic.

While it's too pat, "Little Girl" is several cuts above thrillers in the dopey, bedraggled class recently exemplified by "Burnt Offerings" and "The Sentinel." You may leave feeling disappointed at the way the story is resolved, but you aren't likely to feel like walking out contemptuously long before the denouement.Laird Koenig, who adapted his own novel, works more conventionally than one might wish, but at least he knows how to place one melodramatic foot after the other, a feat of coordination that eludes many people posing as screen-writers these days. Director Nicholas Gessner is deft enough to keep "Little Girl" engrossing from start to finish, and he springs a few witty, creepy surprises.

In her efforts to remain master of her fate and domicile, Jodie Foster is threatened by a pair of undesirables - Alexis Smith as a domineering, bigoted realtor and Martin Sheen as her son, a vicious creep with a yen for little girls - and assisted by a superficially unlikely suitor, Scott Jacoby as a crippled high school boy named Mario, who does magic tricks.

Given the overload of "sensitivity" that surrounds this juvenile Mario the Magician who must hobble around on a lame leg and then contract pneumonia too, it's a wonder Jacoby never seems the least mawkish. On the contrary, his Mario is a remarkably funny, resourceful boy, and the most appealing moments in the film trace the friendship that develops between Mario and the girl, named Rynn, after he catches onto her charade and decides to help her maintain it.

The film really ought to explore this relationship in depth. Foster and Jacoby play very attractively together, and the premise might have ended more agreeably if it had been manipulated as a juvenile romance with undertones of suspense rather than a Gothic murder story with undertones of romance. The outgoing Mario seems capable of drawing Rynn into an orbit that might be more rewarding and the secure than the devious, shaky isolation she's trying to protect. One could imagine these characters in a beguiling variation on the Sleeping Beauty legend, a Sleeping Beauty story about precocious adolescents.

The characters played by Alexis Smith and Martin Sheen ask for drastic comeuppances, especially the latter, who not only makes lewd overtures to the heroine but also tortures and kills her pet hamster. These fairy tale witches in modern dress barely deserve to live, but Koenig might have exercised more restraint in the acts of deploying and eliminating them. The heroine ends up tainted with a good deal of their sadism, a somewhat disagreeable turn of events. It's rather like starting to watch "Wait Until Dark" and then finished up with "The Bad Seed" or "Arsenic and Old Lace."

Jodie Foster's clear-eyed spunkiness and emotional assurance bring more authority and resonance to the character of Rynn that the plot can quite support. At the moment Foster is ideally suited to portray extraordinary kids, and the general idea here is very promising - a precocious girl making trouble for herself as only a precocious girl might be tempted to.

Foster is the least deferential of juvenile actors. Her self-possession lends a special undercurrent of apprehension to the scenes in which she defies would-be intimidating adults like Smith and Sheen. You admire her and yet fear for her. She needs roles that can exploit the challenging, straight-forward aspect of her personality while suggesting the inherent vulnerability of her youth and sex. Rynn isn't an adequate role in the long run, but it suggests the direction filmmakers who valuea resource like Jodie Foster might be interested in pursuing.

'Motel' Vacancies

'Motel' Vacancies

Washington Post, The (DC) - October 25, 1980

Author: Gary Arnold

If a straightforward approach fails, rejection can sometimes be finessed by pretending that you were just kidding.

In show business, this subterfuge comes in handy when a show seems miscalculated or dumbfounding. The obvious explanation is that it's really a deadpan parody, intended to satirize the genre it appeared to be imitating so poorly.

"Motel Hell" has been preceded by rumors that it should be perceived not so much as a straight horror thriller but as a tongue-in-cheek spoof of horror thrillers. The evidence suggests that this interpretation grew out of the good old if-it-doesn't-play-as-a-drama-maybe-they'll-buy-it-as-a-comedy dodge.

The most perfunctory and least imaginative of the recent cycle of horror melodramas, "Motel Hell" may be credited with a fleeting wry touch, but it wears out its welcome by running a minimum of ghoulish stunts into the ground. The title refers to an out-of-the-way hostelry called the Motel Hello; the final letter on the neon sign begins. The owner, Farmer Vincent (Rory Calhoun, now gaunt and white-haired) is a cheerful psycho who uses his motel as a front for a subsidiary enterprise: the preparation of hickory-smoked meats whose savory fame has spread across the nation.

Farmer Vincent's wicked secret is that he not only slaughters the porkers one sees on the property but also lays traps for unwary motorists and visitors, who are planted in a secluded little garden before being butchered and processed into sticks of beef jerky. Farmer Vincent is assisted in his outrages by a stout, malign kid sister, played by Nancy Parsons. They have a kid brother -- a deputy sheriff played by Paul Linke -- who is ignorant of the foul commerce. However, Farmer Vincent sows the seeds of his destruction by taking a fancy to a potential victim, Nina Axelrod, whose ingenuous charms also attract his straight-arrow sibling.

If memory serves, the cannibalistic premise of "Motel Hell" was a staple of "Alfred Hitchcock Presents." Maybe kids will be able to respond to it as a chilling, diabolical novelty, but it seems to me that writers Robert and Steven-Charles Jaffe (the sons of executive producer Herb Jaffe, evidently helping to Get the Boys Started) fail to dust off an accumulation of expository cobwebs or rearrange the creepy furnishings in any fresh or witty manner.

Farmer Vincent's rationale for his homicides is awfully flat -- he claims to be increasing the food supply while reducing the excess population -- and so is much of the picture. There are effectively grisly situations, like the garden of victims with their heads sticking out of the ground, struggling to cry out despite slashed vocal cords, or the dueling chain saws showdown between Farmer Vincent and his brother. However, the longer such spectacles remain in view -- and this movie has a bad habit of stringing everything out -- the more questions they raise and the less sensational they appear.

For example, if planting the live victims is meant to serve a purpose in the hickory-smoking process, it's never explained. The Jaffes haven't thought out the illustrative details contrived around the cannibalism gimmick.

Arbitrary and prosaic, "Motel Hell" conspicuously lacks the satiric logic that helped rationalize the weird, wacko killings in early Roger Corman diversions like "Little Shop of Horrors" and "Bucket of Blood." Not even the motel seems integral to "Motel Hell" when all is bled and done.

Burying Art Alive In ’Avalanche’

Burying Art Alive In ’Avalanche’

Washington Post, The (DC) - September 23, 1978

Author: Gary Arnold

After theater managers add up the receipts, "Quarantine" may seem a more appropriate title for "Avalanche," an inept disaster melodrama now at several obliging, unlucky locations. This fizzled brain-storm from New World, Roger Corman ’s production company looks like a cinch for the first supplement to "The 50 Worst Films of All Time."

Not that "Avalanche" is the sort of terrible movie that cries out to be seen. It lacks the irresistible> transcendent foolishness of the bombastic, egomaniacal duds like "Exorcist II" and "The Trial of Billy Jack" and "Viva Knievel."

Basically a marvel of disorganized exposition and cut-rate disaster effects, "Avalanche" is a low-yield bomb-out.

Given Corman’s reputation for thrift. "Avalanche" poses a kind of chicken-or-the egg mystery did someone in the organization actually consider it timely to slap together a quickie imitation of "Earthquake" and "Airport 75" set at a ski resort in the Rockies? Or did Corman just have some winter sports footage gathering dust and decide that it had to be integrated into a feature at any cost?

Whaever the motives, the result is a shambles. The plot ostensibly a romantic triangle involving Rock Hudson as a dynamic resort developer, Mia Farrow as his on-again, off-again ex-wife and Robert Forster as a rugged outdoorsman never gets off the dime. Ditto for the "subplot" a shameless appropriation of the Spider Sabich-Claudine Donget case with Rick Moses cast as a philandering superskier and cathey Paine as his hysterically jealous girlfriend. Mercifully, the avalanche gets them before they can get each other.

After lurching between expository fragments and winter sports fragments without conveying the faintest illusion that anything of consequence has been depicted, the filmmakers turn to the avalanche in the vain hope that it might bury their mistakes. Instead, it compounds them.

The disaster footaage is faked so poorly that there never appears to be a pictorial connection between the rampaging snow - sometimes falling down real mountains at other times down miniature sets or in tacky optical shots - and the sites and characters it’s supposed to pulverize.

The disaster is reputed to begin when an off-course private plane plows into a snow-capped peak. The alleged destruction seems to cover an indefinably vast area. For all one knows, all of Colorado could be in the path of this elusive cataclysm. Extras keep screaming under the shower of falling snow, but it’s impossible to tell precisely where it came from and how it gets from one victim to the next. TR 3 avalanche

Rock Hudson and Mia Farrow aren’t exactly box-office giants these days, but they’re a little too well-known to lend their floundering, embarrassed presences to a down-and-outer as derelict as "Avalanche." You expect a movie this punk to star names like Edward Obscure and Lana Nobody. Or maybe Rick Moses and Cathey Paine.

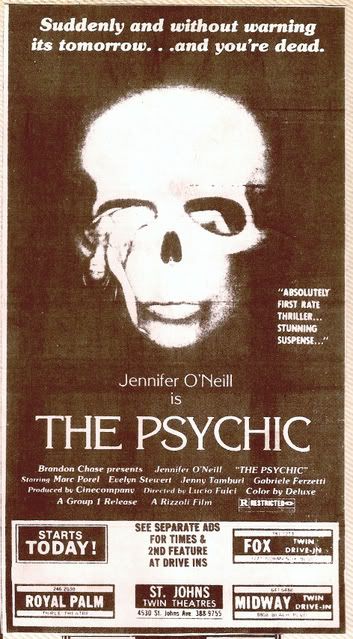

’Psychic’ Shivers

’Psychic’ Shivers

Washington Post, The (DC) - May 1, 1979

Author: Gary Arnold

"The Psychic," on the whole an uneven experiment in terror, had as unheralded an opening as any movie in Washington.Audiences who took potluck on it, however, were probably agreeably surprised by some genuinely clever touches and reflectively sustained shivers.

According to the minimal advertising material available, "The Psychic" was directed by someone named Lucio Fulci , who transcends his overdramatic mannerisms to reveal a talent for orchestrating pictorial suspense. Fulci hits his stride in the last reel or so, when Jennifer O’Neill, evidently lingering in Italy after "The Innocent" and cast as the clairvoyant heroine, is stalked from one old dark premises to another by the killer whose past and future crimes she has envisioned.

Although Fulci plants intriguing clues to the showdown-a shattered wall mirror, a wooden floor lamp with a huge red shade, a yellow-papered cigarette smoldering in a blue ash-tray, a hint of entombment borrowed from Poe’s "Cask of Amontillado"-much of the early exposition requires patience. The sound has the sepulchral quality of Italian post-dubbing. One must also put up with repetitive visual hokum, particularly shots boring in for a look at O’Neill’s all-seeing eyes.

But once the heroine embarks unwittingly on her final rendezvous with the murderer-clairvoyance conveniently fails her at this juncture to make a spine-tingling conclusion possible-Fulci demonstrates a masterful command of timing, mood and seductively menacing images. He seems to turn the corner during a passage that recalls Martin Balsam’s ill-fated walk up the staircase in "Psycho." In this case O’Neill, summoned to a murder house by a possible informant, begins mounting a wide, shadowy staircase and halts at the sight of blood slowly drip, drip, dripping onto the steps from the floor above. When she looks up, the sequence is off and running for perhaps 20 minutes of wittily elaborated hide-and-seek.

Like Dario Argento, the talented but excessive director of horror films like "Suspiria" and "The Bird With the Crystal Plumage," the obscure Fulci seems to have more stuff than he often needs. Still, it’s more amusing and rewarding to play along with the excesses of enthusiasm in a Fulci than to wait for a laborious tease, like John Carpenter of the grossly overrated "Halloween," to get his scare-show off the dime.

One could imagine many other actresses supplying a more entertaining performance as a threatened psychic than O’Neill does. Fulci uses her beautiful but usually impassive face as a decorative object in compositions where darkness and threatening emblems appear to be closing in on its luminous surface.

The little detail of the wristwatch given the heroine by a friend is essential. The timepiece proves one of the more delightful props ever exploited in a movie thriller. It plays a critical role on two occasions in the closing minutes, the second cueing a stunning freeze-frame fade-out.

Cut! Print It! (Scenes From 'The Boogey Man')

Cut! Print It! (Scenes From 'The Boogey Man')

Washington Post, The (DC) - September 23, 1980

Author: Gary Arnold

No historic opportunity will be lost if the La Plata, Md., Chamber of Commerce declines to publicize the fact the "The Boogey Man" was shot there.

Apart from a house obviously chosen for its resemblance to the house in "The Amityville Horror," the picturesque aspects of "The Boogey Man," an absurd but proficiently grisly horror cheapie now at area theaters, have little connection with the locale.

If director Ulli Lommel has a specialty, it's sadism. Although his continuity is a tattered patchwork of devices borrowed from horror thrillers as venerable as "Dead of Night" and as recent as "Halloween" and "Alien," Lommel can make you recoil and take appalled notice at certain highlights: The heroine being dragged across the floor while bound and gagged and clad only in her undies; a murder victim simultaneously displaying bare breasts and scissors embedded in her neck; the undeniable piece de resistance -- comparable in its way to the severed head in "The Omen" -- of a teen-age couple being skewered through the mouths to achieve a literal kiss of death.The latter sensation calls for a snappier title than "The Boogey Man," which never seems justified anyway. "Kiss Kiss Stab Stab" would be more the ticket.

The terrors supposedly originate in a traumatic childhood episode, depicted in a prologue whose events and background music blatantly echo "Halloween," presumably for quick identification with the same basic target audience -- shrieking teen-age girls and their wisecracking dates. A little boy and girl are shown peeping through a living room window at a man and woman preparing to get down to lewd recreation. The woman spots the children, who are revealed to be her own. She watches approvingly as her lover binds and gags the boy as a punishment for allegedly chronic peeping.

The little girl, merely confined to her room, sneaks out of bed, picks up a large carving knife in the kitchen and cuts her brother loose. We follow two little hands clutching the knife as it goes upstairs and enters the mother's bedroom. A large rectangular wall mirror reflects the ensuing murder, in which the boy repeatedly plunges the blade into the lover's back. Shrieks and fadeout.

Fade-in 20 years later. The little girl has grown into a young wife and mother named Lacey, played by an attractive actress named Suzanna Love, who suggests a cross of Lindsay Wagner with Patty Duke (and happens to be the director's wife). Lacey lives with her husband, son and brother Willie, rendered speechless since the violent night long ago, in a large country house. r

Lacey is disturbed by the news that her disreputable mother desires to reestablish contact. As she watches the meat being carved at supper, she's all too discernibly haunted by memories of another carving knife. Sensing her discomfort, the helpful husband, an indispensable dope, insists that she confront and exorcise lingering bad memories.

He takes Lacey to a shrink-hypnotist played by John Carradine, doing the "guest star" bit that Boris Karloff used to do in Roger Corman potboilers like "The Terror." Under hypnosis, Lacey begins roaring like the demon Pazuzu in "The Exorcist." Chalk up another gratuitous crib from a hit horror movie.

Still not satisfied, the husband drives Lacey back to the original murder house, now occupied by another family but up for sale. The parents are out, but Lacey and spouse are admitted by the kids, a pair of teen-age sisters and their mischievous kid brother, smartly portrayed by David Swim. Entering the murder room, Lacey is soon terrorized by the mirror, which reflects the killing with maddening fidelity. To protect herself from its spell she shatters the glass with a handy chair.

Surpassing even himself, the husband apologizes for Lacey's rashness and then insists on gathering up the pieces and reassembling the mirror at home, the better to purge his beloved of all those frightening phantoms. One gathers that he's a whiz at jigsaw puzzles, because the jagged fragments of the mirror are back together in no time.

The remainder of the movie is wackily ratonalized by this loose connection to the haunted mirror episode from "dead of Night." In Lommel's variaton the littlest shards and slivers of the mirror are endowed with supernatural potency, luring anyone near them into deathtraps or homicidal rages.

The devices never make a sliver of sense, but they allow Lommel and his collaborators (two local filmmakers, cinematographer David Sperling and editor Terrell Tannen, were members of the crew) to assume fitfully effective attack positions. It's difficult to judge whether the payoffs would be enhanced by a more plausible or clever pretext. Probably not. The shocks might even be curiously diluted by a little preliminary sophistication. "The Boogey Man" achieves a certain vicious distinction by putting the occasional spectacular kink in an otherwise motely fabric.

'SLAP SHOT': Vulgar, Rowdy, Mixed-Up and Commercial Mischief

'SLAP SHOT': Vulgar, Rowdy, Mixed-Up and Commercial Mischief

Washington Post, The (DC) - April 1, 1977

Author: Gary Arnold

"Slap Shot," opening today at the K-B Fine Arts, reunites Paul Newman and George Roy Hill, the star-director team of "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" and "The Sting," in a vulgar, rowdy, mixed-up commercial entertainment.

This tendentious comic fable about the comeback of a failing minor-league hockey team under the desperately mischievous leadership of Newman, cast as an aging player-coach called Reggie Dunlop, finds the star in clever, winning form while the director seems to be running a deliriously hypocritical fever.

>

"Slap Shot" comes at you like a boisterous drunk. At first glance it appears harmlessly funny, in an extravagantly foul-mouthed sort of way. However, there's a mean streak beneath the cartoon surface tha makes one feel uneasy about humoring this particular durnk for too long.

Hill has tried to combine a crowd pleasing style of profane, slapstick sporting humor, reminiscent of the approaches that proved popular in such movies as Robert Altman's "M*A*S*H" Robert Aldrich's "The Longest Yard" and Michael Ritchie's opportunistic, ineffective gestures of social criticism, perhaps inspired by Altman's "Nashville." Although the gags and digs tend to be equally gratuitous, Hill is vastly more proficient at the former.

Luckily for the filmmakers, audiences may decline to equate themselves with the hockey fans shown clamoring for brawis and buffoonery. Alternately closnish and snobbish, a gut and turning on us for being sus-"Slap Shot" keeps inviting us to bust ceptible to the invitation.

Despite a record of success in his profession that would seem enviable to most people, George Riy Hill may crave a kind of "serious" recognition that has eluded him. Strange as it seems, the popularity of films like "Butch Cassidy" and "The Sting" may not compensate for the failure of films like "Slaughterhouse-Five" and "The Great Waldo Pepper," which Hill might have considered more personal and audacious projects.

There's strain of discontent in the movie that seems unwarranted and damaging. It's as if Hill couldn't suppress his resentment at giving public what he presumes it wants.

Shot largely on location in Johnstown, Pa., "Slap Shot" is an episodic account of the last season of the Charlestown Chiefs, a mediocre club which begins to win games and revive fan interest after adopting a pugnacious, bullying style of play. The transformation is improvised by Dunlop, who realizes that he has nothing to lose, since the management has decided to fold the franchise. Dissembling on two fronts, Dunlop provokes situations that turn the Chiefs' games into rabble-rousing free-for-alls and plants a rumor that the team may be mvoed to Florida with a bullible sports reporter.

Like their protagonist, Hill and screenwriter Nancy Dowd, whose brother Ned played minor-legue hockey with the johnstown Jets, try to engineer a con, but their motives and techniques are less respectable. Dunlop's antics may make a mockery out of the games, but there's an admirable side to his deviousness: Dunlop is scheming to save the jobs of his players as well as his own job.

Newman makes DUnlop such a transparent, ingratiating deceiver, a battered, puzzled but indomitably zesful and resourceful jocks, that it's impossible to resent most of his subterfuges. The filmmakers exploit Dunlop far more questionably than he exploits the Chiefs and their followers, because they attempt to stretch the club's preposterously depicted success story into a would-be devastating sociaal parable.

Dowd's writing demonstrates certain elastic properties, but it can't be stretched to encompass a cherent or persuasive point of view.It's astonishing that the film keeps going on zany blackouts and profane zingers, but it somehow does. The filmmakers can't conceal the fact that they haven't sustained a single plot thread of relationship, yet they charge "Slap Shot" with aggressive energy.

One can detect sharper sources of conflict in the way the filmmakers treat the story and characters that in the way the characters treat each other. Initially we're led to believe that the Chiefs are folding because layoffs at the town's steel mill will inevitably kill the box office. The dubious assumption is forgotten later on. The team becomes an outrageous success, but the apathetic owner, a divosrcee played by Kathryn Walker, informs Dunlop that she's closing shop for tax purposes, on the advice of her financial advisors.

This remarkably ugly scene is orchestrated for insult. The owner patronizes Dunlop, who retaliates with a vicious parting shot, the most obsence remark in a script that goes out of its way to sound indiscreet. Dunlop returns to the locker room to grumble, "We were never anything but a rich broad's tax write-off." Why weren't the hapless Chiefs a satisfactory tax write-off? Could Dunlop have messed up by turning them into a hit? If so, why wasn't this potential irony worked imto the plot?

In a similar respect, presumably key relaionships remain unexplored. You expect scenes that will clarify the apparent conflict, between Michael Ontkean, cast as the team's smart star player, Ned Braden, and Lindsay Crouse, who plays his discontented wife. They never materialize. neither do the scenes that should develop the relationship between Dunlop and Braden, who sees through the coach's schemes from the start and refuses to play along. Even the fact that Mrs. Braden moves in with Dunlop seems inconsequential.

Dowd's writing has a peculiarly nebulous quality: It sound brassy but leaves no reverberations. Ultimately, the film seems so shallow that one can't even be certain what Braden's climactic beau geste, a striptease on the ice, is supposed o signify. If may be a gesture of ironic contempt or a gesture of ironic contempt or a gesture of whimsical resignation. For reasons that remain bafflibg, it appears to patch up his marriage.

"Slap Shot" is a joyride conducted by drivers who betray an undercurrent of hostility toward their passengers. The profanity expresses more that documentary fidelity to the vocabulary of jocks. It's an aggresive outlet for the filmmakers, too. Once you hop on, it's advisable to concentrate on the gratuitously funny aspects of the ride and to avoid taking the hostility personally.

People are more likely to be upset by the movie's dialogue sthan its split personality. Even Newman's witty acting may suffer from the fact that it's embedded in a deliberately offensive context. Newman is literally a diamond in the rough, and it requires a certain forebearance to separate his quality from the surrounding raunch.

The ultimate weakness of the film is that it's claculated to be a self-fulfilling cynical prophecy: Box-office success can be taken as justification of the assumption that moviegoers only want to play dirty. Well, not necessarily; it all depends. It is unreasonable to expect the public to feel guilty because Hill and Dowd insist on alternately stroking and slapping the hands that feed them.